Women’s soccer sophomore midfielder Alexis Williams was playing with her club high school team at a tournament in Colorado when she found she could not keep up her endurance on the field.

“It was the weirdest thing because I’ve never had problems running or anything, but I would have to stop every second,” she said. “I couldn’t run.”

Williams knew she was physically fit, but questions from her coaches asking if she was out of shape frustrated her – especially because being quick on the field was a hallmark of her play.

She forgot about the incident when she returned home to New Jersey, where she was able to return back to her normal ability on the field.

But the moment in Colorado would return to Williams’ mind when she went in for a sickle cell trait test before her freshman year of college – an NCAA requirement for athletes before their first season – and it came back positive.

“I was a little bit scared at first because I didn’t really know much about it,” she said. “I mean I had heard of it, but I didn’t know that it would affect me playing soccer.”

Sickle cell trait occurs when a person inherits both a sickle cell and a normal hemoglobin gene. Possessing two sickle cell genes results in sickle cell anemia, which is when blood cells form in a crescent shape that increases clotting and decreases oxygen flow.

Sickle cell trait, what Williams tested positive for last year, tends to be asymptomatic.

Williams was first tested for sickle cell trait when she was an infant, alongside her older and younger sisters. Williams’ mother took her three daughters to be tested for the sickle cell gene because their father has sickle cell anemia.

The results for Williams and her younger sister came back negative, while her older sister tested positive for the trait. But the positive test that the doctors believed to belong to her older sister years ago actually belonged to Williams, she said.

Williams led an active childhood despite unknowingly having sickle cell trait. She tested out softball, lacrosse, basketball, soccer and track, before continuing track and soccer into her high school years. She drew collegiate coaches to her soccer games as early as her freshman year.

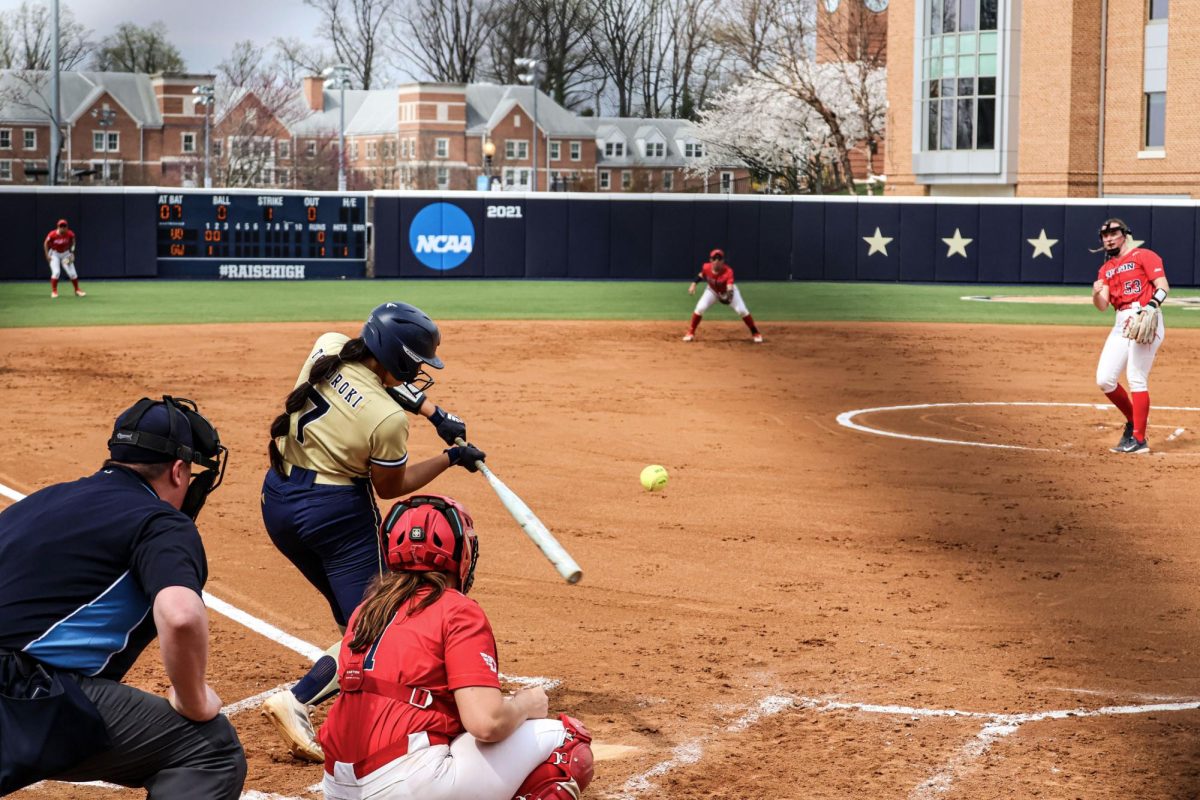

[gwh_image id=”1065527″ credit=”File Photo by Arielle Bader | Staff Photographer” align=”none” size=”embedded-img”]Sophomore midfielder Alexis Williams leads women’s soccer in goals scored with four.[/gwh_image]

At GW, Williams has started in seven of eight games this season for the Colonials. She leads the team in goals scored with four and is one of three players to have tallied an assist.

“Conversations were had earlier in the season and she knows how important she is to the team,” head coach Michelle Demko said.

The biggest risk factors that could lead to complications with sickle cell trait are low oxygen levels, dehydration and high altitudes – like what Williams experienced in Colorado.

When experiencing symptoms, Williams said her heart rate spikes to more than 200 beats per minute, well over the average of 60 to 100 beats per minute. Her chest tightens and she said she would sometimes feel lightheaded and on the verge of passing out.

Williams said growing up, her mother made her drink a full container of coconut water before every soccer game, but she stopped when she got to college because she never liked the taste.

“That’s when I started realizing that I had a problem running and the heat got to me,” Williams said.

Now, she drinks a bottle of Pedialyte or Powerade Zero the night before every game and three on the morning of a game to ensure she is fully hydrated to prevent symptoms.

Demko, who took over the women’s soccer program in April, said she was immediately informed of Williams’ condition the first day she came to train the team at the end of the spring season. She said she sat down with Williams and said there would be “no questions asked” if Williams ever needed to take a break during a game.

“She’s a competitor, she doesn’t want to step away at all,” Demko said. “So it’s just really reminding her and asking her ‘how are you feeling, do you need a break?’”

During soccer games, athletes are not permitted to return to play in the first half if they are substituted out, but athletes playing with sickle cell trait can re-enter the game if they need to come out because they are experiencing symptoms, according to NCAA rules.

Graduate assistant athletic trainer Adrienne Mendel carries a copy of the rules with her at all games in case referees are unfamiliar with the guidelines, Demko said.

Williams said it can be hard for teammates to understand why she might not seem to be hustling on every play, but she explains that her decreased speed is not because of a lack of effort.

Although the initial moment of diagnosis was shocking for her, Williams said the coaching staff and athletic training team at GW have made her feel more secure.

“I’m not afraid anymore,” she said. “I just know that I’ll be OK because I have good support around me.”